Spoiler alert! This story is mostly about aerodynamics, from downforce to drag, venturis to ventilation, and splitters to, well, spoilers.

If you don’t recognise Richard Hill, you’ll know his work: the Lotus Evija hypercar, for instance, or the bicycle Chris Boardman rode to Olympic glory. These are just two highlights of a lifetime at Lotus, studying the science of speed.

Having joined Lotus in 1986, Richard has risen to the role of chief aerodynamicist. Or Chief Engineer of Aerodynamics and Thermal Management, to be exact.

Here, he talks us through a remarkable career, ending with thoughts on where car design goes next. And it all began with ‘Wet Nellie’…

His dad borrowed Roger Moore’s Esprit

“I can remember the exact moment of deciding I wanted to work for Lotus,” reminisces Richard.

It was 1977, the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. But while Johnny Rotten sneered “there is no future in England’s dreaming,” Richard thought otherwise. He dreamed of being Bond, James Bond.

“My father was general manager for a paint company that supplied Lotus,” he explains. “Somehow, he managed to borrow the Esprit S1 from The Spy Who Loved Me, released that same year, for display at a show. I’ve no idea how he pulled it off.”

Known as ‘Wet Nellie’ and driven by Roger Moore, the aquatic Lotus captured the young Richard’s imagination. “It inspired me to pursue a career in cars.”

His first job for Lotus was a Corvette

Richard’s big break came nine years later – but his first job at Hethel wasn’t a Lotus.

After studying aeronautical engineering and composites at university (including work on the Ralt RT30 Formula 3 car) his wife-to-be spotted a recruitment ad for Lotus. “They were looking for engineers, so my first job wasn’t in aerodynamics.”

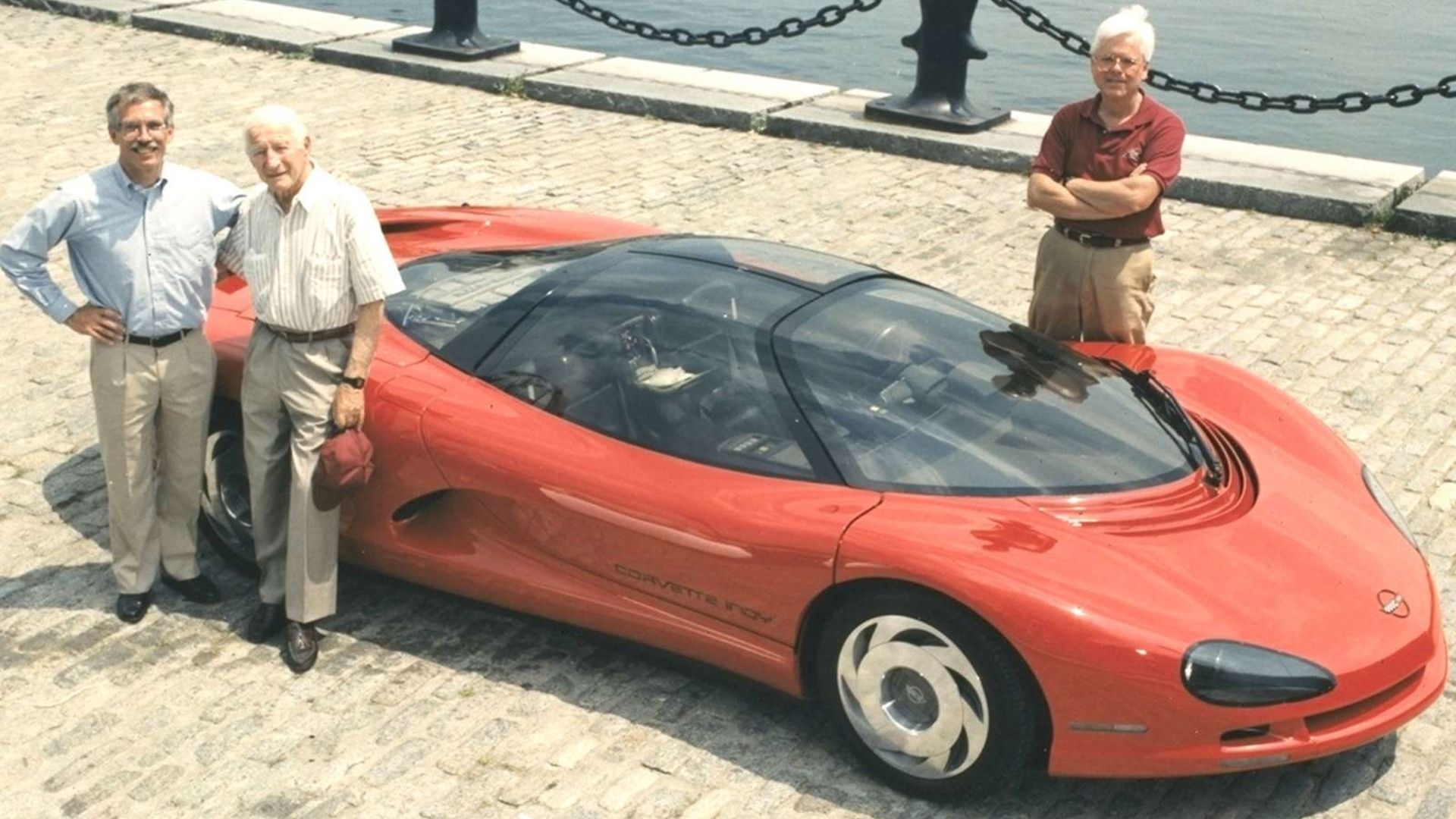

Instead, Richard was tasked with designing a torque tube for a Chevrolet Corvette concept – likely the 1986 Indy (pictured) or subsequent 1990 CERV III. Lotus, you will recall, was owned by General Motors at the time.

Both the Indy and CERV III were futuristic, mid-engined design studies. Ironically, it would be early 2020 before a mid-engined Corvette finally reached production.

‘Aerodynamics was very important to Colin Chapman’

No car company is so inextricably linked with aerodynamics as Lotus. Along with ‘lightweighting’ (used as a verb at Hethel), it defines the marque’s approach to performance.

“Aerodynamics was very important to Colin Chapman,” says Richard. “In the Formula One world, Lotus pioneered the use of wings and ground-effect – with amazing success.”

A few more from the Classic Team Lotus workshop.

Clockwise from top: Type 49, Type 94T, Type 86 (love that Team Essex livery!) and the banned ‘twin chassis’ Type 88. pic.twitter.com/NKIUwHFcQR

— Tim Pitt (@timpitt100) December 9, 2019

The trophy cabinet at Classic Team Lotus (located opposite the new Evija production facility) includes silverware from seven F1 constructor’s championships, won between 1963 and 1978.

Notable high-points include the 1963 Lotus 25 (the first racing car with a fully stressed monocoque chassis), 1968 Lotus 49 (the first to use an aerofoil wing) and 1977 Lotus 78 (the first with ground-effect downforce). All these innovations later appeared on Lotus road cars.

He helped design Team GB’s Olympic bike

“My claim to fame is being the second person Chris Boardman hugged when he won Olympic gold in Barcelona,” says Richard. “His wife was rightly first!”

The famous Lotus Type 108 bicycle used carbon composites and advanced aerodynamics, helping Boardman to gold in the 4,000m pursuit – and a new world record. “It was a good platform to demonstrate our engineering skill.”

Those skills were called upon again for Team GB’s latest track bike, a joint-project with Hope Technology. Pictured above with Ed Clancy, it’s a more conventional design than the revolutionary 108.

“Racing bike design took a big step backwards after the 108 and 110,” Richard explains. “We went from monocoque frames to a more traditional tubular, triangular design. That was dictated by regulations, and demands a different approach. With the 108, we aimed to separate the airflow around the bike from the rider. Now, we treat man and machine as one.”

The Esprit is very close to his heart

Asking Richard to name his favourite Lotus elicits a long pause. So we settle for a selection of cars that have meant the most.

“The Type 18 in 1960 was the first true mid-engined Lotus Formula One car, which led to our first mid-engined road car: the Europa of 1967. My favourite of those was the JPS twin-cam special of the early 1970s. They were the genesis of all mid-engined Lotus sports cars.”

S3 Lotus Esprit Turbo on the King’s Road.

Have I won car-spotting for today? pic.twitter.com/sTCe7O894E

— Tim Pitt (@timpitt100) January 18, 2020

Despite his admiration for the Europa, though, I sense the Esprit tugs hardest at Richard’s heart strings. “I saw that car through much of its production life and had some amazing road trips. Believe it or not, we worked through 17 different rear wing designs between 1987 and 1993. Each one had a nickname”.

Honourable mentions also go to the Elise (“The first Lotus engineered with zero lift. We spent so many hours in the wind tunnel”) and Evora (“It developed our dynamic handling strategy”).

‘Lotus looks at aerodynamics differently’

“Most companies focus their efforts on drag reduction: achieving a low Cd figure. That’s what car buyers tend to look at”.

A low coefficient of drag helps reduce fuel consumption and increase top speed. However, as Richard explains, Lotus looks at the bigger picture.

“Inspired by motorsport, the balance of downforce and lift is our main priority. It’s about high-speed stability, both in a straight line and when cornering. We minimise drag where we can, but that’s our secondary focus.”

This philosophy is taken to extremes in the new Evija, a car that “literally breathes the air”.

The Evija is ‘a fighter jet in a world of kites’

Unless you have seen self-isolating for the past year, you’ll know the 2,000hp Lotus Evija is the most powerful production car ever. The £2 million electric hypercar will hit 62mph in ‘less than three seconds’ and exceed 200mph.

Such performance requires a radical approach to aerodynamics. “The front acts like a mouth. It ingests the air, sucks every kilogram of value from it – in this case, the downforce – then exhales it through that dramatic rear end.”

So, here’s the new 2000hp, £2 million Lotus Evija – the most powerful production car ever.

Rear ‘three-quarter venturis’ are its most distinctive feature – ringed by red LEDs like afterburners. pic.twitter.com/fiLJMjCD8Z

— Tim Pitt (@timpitt100) July 16, 2019

The word “porosity” crops up frequently, particularly with reference to the dramatic rear venturis. “Without them, the Evija would be like a parachute, with them it’s a butterfly net. And they make the car unique in the hypercar world.”

Lotus hasn’t revealed drag or downforce figures for the Evija yet, but it goes way beyond conventional sports cars. “It’s like comparing a fighter jet to a child’s kite,’’ says Richard.

Electric tech will change the shape of cars

Few cars will harness airflow like the Evora – “It wouldn’t be possible in a car you drive to the supermarket with a family of five” – but elements of its design will appear on future models. Indeed, the new Lotus Emira already shows a clear influence.

“We’ve learned a lot from this project,” Richard adds, “and some of its aerodynamic concepts will be carried forward.”

Indeed, Richard is excited about the future of car design in a world increasingly populated by EVs. “Packaging an electric car is very different. You don’t have a bulky engine and cooling system to accommodate. There’s more freedom.”

With huge investment from parent company Geely, the future looks bright for Hethel. And thanks to Richard and his team, any new cars should stay faithful to Lotus’ aero-led legacy.

Who knows, maybe even 007 will drive a Lotus again. The Evija would look awesome as submarine…

ALSO READ:

Lotus Elise Sport 240 Final Edition review

The most exciting Lotus road cars

[…] Die Another Day certainly isn’t the best Bond film – and frankly, Pierce Brosnan isn’t the best Bond. But the Aston Martin Vanquish might be the coolest car modified by Q Branch. […]

[…] between the bannisters, then cartwheeled down the stairs. The Matchbox model in question was ‘Wet Nellie’, James Bond’s submarine supercar from The Spy Who Loved Me. Fittingly, I think it ended up in […]

[…] Lotus tradition. As such, it would have sat between the Type 110 (a record-breaking carbon fibre bicycle) and Type 112 (a stillborn Lotus F1 car for the 1995 […]