On 11 May 1994, Autocar & Motor magazine published its landmark road test of the McLaren F1. As a wide-eyed and car-obsessed 15-year-old, I spent £1.35 of my pocket money on a copy and devoured every word. ‘What you are about to read is not simply the fastest road test in history,’ trumpeted the opening line. ‘It is, in all likelihood, the fastest road test there will ever be.’

At the time, I believed it. The 627hp, £540,000 F1 was so far beyond the supercars of its era – the Ferrari 512 TR, Lamborghini Diablo, Bugatti EB110 and Jaguar XJ220 among them – that it was arguably the first hypercar. At Bruntingthorpe airfield in Leicestershire, it recorded a 0-100mph time of 6.3 seconds, a standing quarter-mile in 11.3 seconds and 0-200mph in 28.0 seconds. Writer Andrew Frankel described the experience as ‘so fast that it’s actually uncomfortable’.

Today, there are family SUVs with more power and accelerative ability than the F1. And Autocar’s road test records have just been smashed by another British hypercar: the 2,039hp, £2.4 million Lotus Evija. It blasted to 100mph in 4.8 seconds, a standing quarter-mile in 9.5 seconds and 200mph in 13.0 seconds. Saying so seems sacrilegious, but those numbers make the McLaren look, well, a little lethargic.

Six years in the making

I first encountered the Evija when it was revealed to the world’s press in London in 2019. Lotus had recently been acquired by Geely – a Chinese conglomerate that also owns Volvo and Polestar – and chairman Li Shufu wanted a halo car to signpost the marque’s electric future. With radical, aero-sculpted styling and more power than any production car in history, the Evija (say it ‘ev-eye-ya’) fitted the bill perfectly.

A lot has happened since that feverish night six years ago. The UK government brought forward its ban on new petrol and diesel cars to 2030. Lotus has launched two electric vehicles, the Eletre SUV and Emeya saloon, both of which are selling slowly. And various battery-powered hypercars, such as the Rimac Nevera, Pininfarina Battista and now-abandoned Porsche Mission X, have tried and failed to ignite the public’s imagination.

After a long and tortuous gestation, the Evija is finally ready, but has its era-defining ‘McLaren F1 moment’ already passed? There’s only one way to be sure…

Purple reign

The sprawling Norfolk sky is bruised by leaden clouds as I arrive in Hethel, home to Lotus Cars since 1966. I’m greeted by design director Russell Carr, a 35-year veteran of the company. “The Evija really was an explosion of creativity,” he tells me. “A hypercar is the pinnacle for a designer. It had to be beautiful, innovative, memorable and thrilling. People don’t buy these cars for rational reasons.”

Carr’s guiding principle was “porosity” – i.e. allowing air to flow through the Evija’s body to reduce aerodynamic drag. It’s an idea best exemplified by the curved venturi tunnels that hollow-out its haunches. Ringed by red LEDs, they resemble glowing jet afterburners. A hydraulically adjustable rear wing and F1-style DRS system also help to generate downforce: up to 1,500kg at a top speed of 217mph.

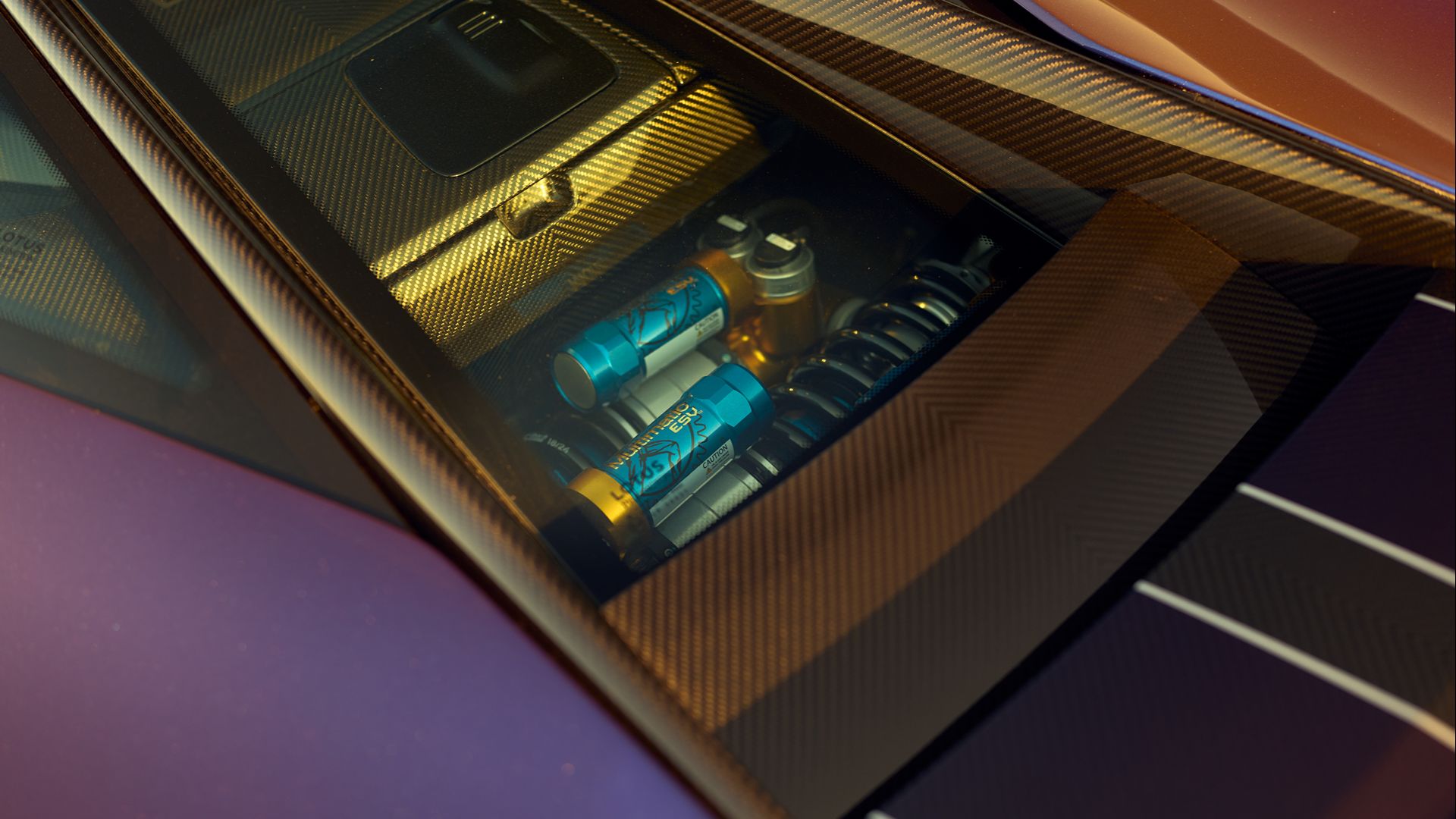

We then walk around a ‘naked’ Evija without body panels. Its carbon fibre monocoque weighs just 120kg and supports a mid-mounted 93kWh battery pack – “located centrally to lower the driving position and reduce polar moments of inertia” – along with two gearboxes and four electric motors. Inboard suspension by Multimatic reduces turbulence around the wheels, with motorsport-style heave dampers to keep the car stable when accelerating and braking. Everything looks as tightly packaged as possible. “A Lotus should be like a packet of Pringles, with everything nested together and no wasted space,” says Carr.

My Evija is waiting outside, wearing a custom shade of ‘Violaceus’ pink-to-purple flip paint. We might be a few miles south of Norwich, but it looks as exotic and outrageous as anything from Maranello or Sant’Agata. Even the Lotus factory workers, taking their lunch break from building Emira sports cars next door, wander across for a closer look. They share a palpable sense of pride in the project.

Inside the Lotus Evija

Acutely aware of my audience, I lift the dihedral door, twist my hips and drop inelegantly into a sparsely padded seat. As the first flecks of rain spatter the windscreen, I try not to dwell on the Evija’s seven-figure price tag, or the immense power I’m about to let loose. EVs are a doddle to drive, right?

Like a sci-fi Lotus Elise, the Evija’s interior looks pared-back and functional. Its dashboard mainly consists of a bracing beam that contains all the ventilation ducting – “Colin Chapman thought every component should do more than one job,” explains Carr – plus a slim central spar dotted with hexagonal haptic touchpads. The overhead console, I’m told, is a nod to the roof-mounted stereo in the classic ‘Essex’ Turbo Esprit. Three digital screens take the place of exterior mirrors, but there is no supersized iPad to distract you from the job at hand. A small screen behind the rectangular wheel delivers essential data and nothing more.

A manettino dial offers a choice of five drive modes. Range mode limits the car to 80mph and is essentially a limp-home setting for when you need to conserve every kilowatt. The liquid-cooled battery manages 195 miles in the official WLTP test, although 150 miles between stops is probably more realistic. Clearly the Lotus is no continent-crossing grand tourer, even with a charging speed of 350kW to allow a 10-80 percent fill-up in 15 minutes. At maximum load, the battery lasts for eight minutes before limiting the car’s performance for its own preservation.

Player one: ready

The next step up from Range is City mode (700hp), followed by Tour (1,400hp). You need to select Sport or Track to harness all 2,039 horses. However, Track mode isn’t technically road-legal, as it requires removing the rear number plate so the diffuser flaps can fully elevate. Lotus hasn’t quoted any lap times, but John Farn-Ramsay, principal engineer for vehicle dynamics, says he can complete Hethel’s test track in about 1min 20sec – fully 10 seconds quicker than the 400hp Emira Turbo SE. He also reveals that, in high-speed testing at Nardo, a derestricted Evija saw the far side of 250mph.

Semi-slick Pirelli Trofeo tyres are decidedly suboptimal on damp tarmac, so I proceed with caution, building up through Range, City and Tour modes as I learn the lines and braking points around Hethel – a fast-flowing circuit used to hone every Lotus since the Seven. John helpfully points out the 180-degree Rindt hairpin at the end of the Mansell Straight, which has no run-off – just a low fence and some very substantial trees. I make a mental note: don’t get cocky.

Despite weighing in at 1,890kg, or more than two S1 Elises, the Evija still moves with a litheness and fluidity that is quintessentially Lotus. Its electro-hydraulic steering bristles with detail, bearing comparison with modern McLaren supercars, and it turns in with strident enthusiasm – so much so that I’m forced to take a breath and relax my inputs. For all the computing power at work, constantly varying the torque delivered to each driven wheel, this doesn’t feel like a video game.

Unleashing all 2,039hp

Its soundtrack is unsynthesised, too: a shrill wail in surround-sound from the four motors, which swells into a rabid, maniacal scream. “Our other EVs are almost silent, but in the Evija you really hear your speed,” yells John over the clamour of excited electrons. It’s not as visceral as a V10, or as multi-layered and musical as a V12, but it’s unique and authentic. Fake engine sounds? It isn’t the Lotus way.

After a few laps, it’s time to switch into Sport mode and unleash the Evija’s full fury. I slow to about 20mph, steady my nerves, then flatten my right foot. Whooooaah! If driving a McLaren F1 flat-out is ‘uncomfortable’, this borders on assault – a violent kinetic energy that pummels you into your seat. At lower speeds, the electric motors are limited by traction, but more torque is fed forwards as you go faster, so the dizzying, disorientating rush just keeps on building. Throttle response and acceleration at three-figure speeds are otherworldly: the Lotus seems to laugh in the face of physics. Yet the evidence is there in Autocar’s figures: that preposterous 0-200mph figure of 13.0 seconds is less than the time it takes to read this paragraph.

I’m touching 150mph on the back straight before leaning hard on the progressive, regen-free brakes at the chicane (added to the circuit after a hard-worked Lotus Carlton cooked its discs and ended up half-way across a neighbouring field). As I start to push in the corners, I can sense the torque vectoring at work, shuffling output across the axles to haul the car inwards towards each apex. Without it, I suspect the Evija would be almost undrivable for mere mortals, but the software spares your blushes, managing the complex interaction of power, traction and grip in a way that feels natural and confidence-building.

Can emotion be electric?

Ironically, the place where confidence finally gets the better of me is exiting the Rindt hairpin, where I punch the throttle slightly too soon, sensing the rear tyres squirm and the tail step sideways before the stability control cuts in. Phew. It feels like an apt moment to pull into the pit lane and swap seats with John. He can show me how it’s done properly.

The next few laps are a blur, knuckles white around the grab handle, body braced against the seat, but I’m left in awe of both the car and the legendary ability of Lotus test drivers. John is nudging 175mph before a brutal brake for the chicane and using every inch of available asphalt. He’s somehow both smooth and aggressive, getting the car to drift and rotate around its axis in a choreographed dance that would earn a ‘10’ from the judges on Strictly. I’ll be honest, it left me feeling quite queasy. The Evija does ‘shock and awe’ like no other car I have experienced.

Back to the McLaren F1. When I was 15, it was the fastest supercar (or indeed hypercar) of them all. In my eyes, therefore, it was automatically the best. Nowadays, I’d like to think my opinions are more nuanced, and it seems those of hypercar buyers are too. In a world where a mass-produced Tesla can blast you from zero to illegal in less than three seconds, raw speed has been devalued. Emotion matters more.

Verdict: Lotus Evija

Lotus won’t say how many Evijas it has sold, but the intended production target of 130 cars – reflecting the project’s ‘Type 130’ codename – now looks extremely unlikely to be achieved. Meanwhile, every new V12-engined hypercar seems to sell out within seconds. Enthusiasts, it seems, just can’t get excited about electric cars.

The irony is that the Evija is exciting – wildly so if you have a racetrack to hand – and makes a worthy addition to any stable of petrol-powered exotics. Also, lest we forget, McLaren struggled to shift the F1 when it was new, eventually building just 64 standard road cars. So, perhaps rather than turning up late, Lotus has peaked too soon. When a generation of new car enthusiasts raised on EVs look back, will they put the Evija on a pedestal?

It’s impossible to know, and I expect the Lotus will remain a footnote in hypercar history. However, I’ll stick my neck out and predict this is the fastest road car I will ever test. Now, wait for progress to prove me wrong…

ALSO READ:

Lotus Theory 1 concept signposts future of electric sports cars